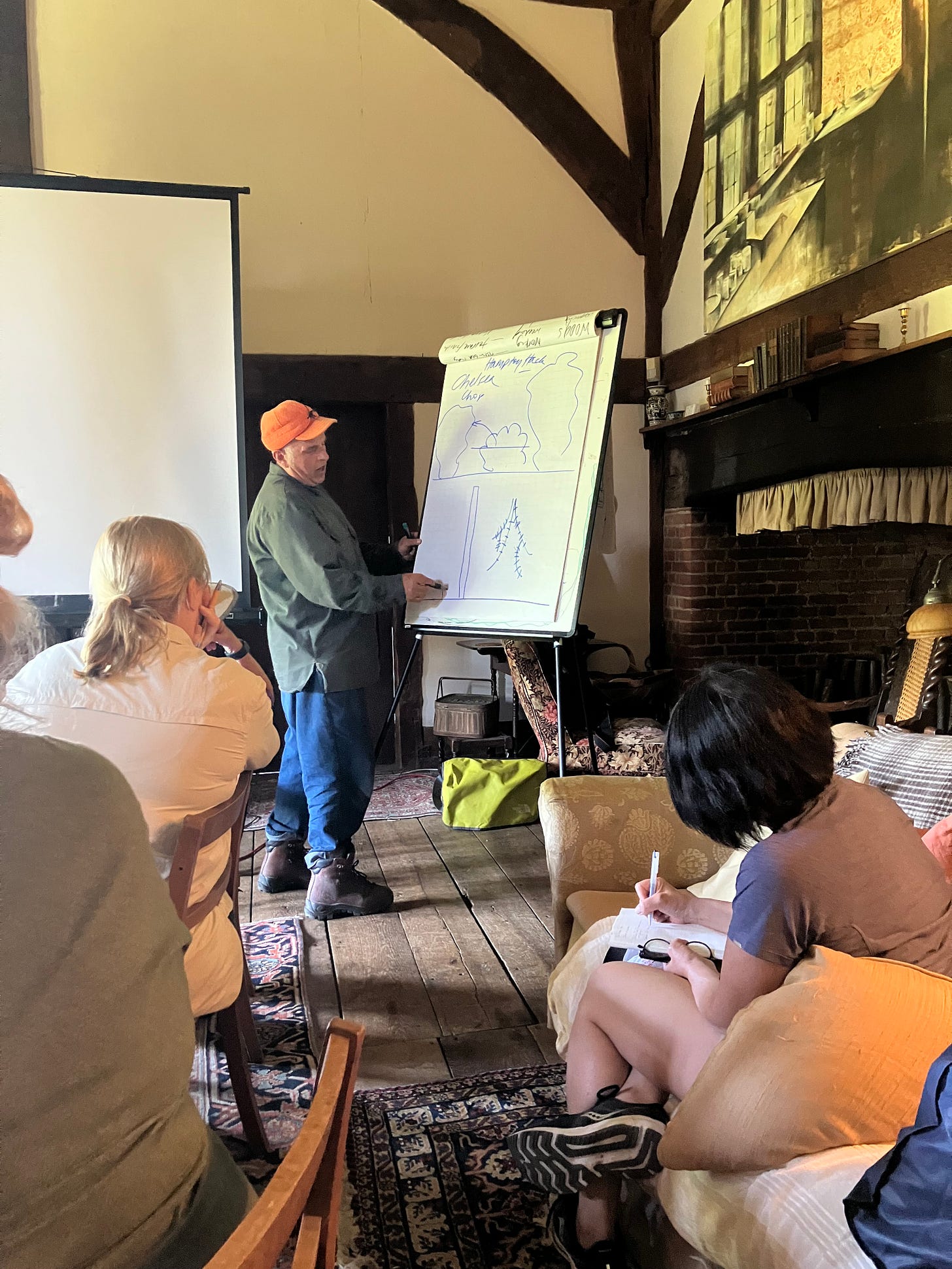

I had the great privilege this summer of participating in a week-long horticulture symposium at Great Dixter, in my opinion England’s most extraordinary collection of gardens. The symposium is led by the third generation steward of Dixter, internationally regarded gardener Fergus Garrett and his extraordinary team.

Dixter is located on the southeast coast of the UK near Rye and was the home of renowned plantsman Christopher “Christo” Lloyd (1921-2006). The property entails about seventy acres, including five acres of cultivated gardens, with the balance given to numerous outbuildings, a nursery, and managed natural meadows and coppice woodlands.

The main house, a half-timber manor house, dates to the 15th century and includes a substantial additional wing and addition of a 16th-century Yeoman’s Hall, salvaged from the nearby town of Benenden. Great Dixter is the result of a foundational vision set by Christo’s parents, Daisy and Nathaniel Lloyd, who bought the property in 1910. At that time, it was just the Medieval manor house (in poor condition) and farmland. The Lloyds hired renowned architect Sir Edwin Luytens, a leader in the English Arts & Crafts movement, to restore and expand the main house. Between 1910 and 1912 Luytens added the wing, oversaw the restoration of the original hall, the reconstructed incorporation of the Yeoman’s Hall and, most significantly, the layout of extensive garden rooms surrounding the house. Nathaniel was an enthusiast for topiary, and amplified the walls and paths laid out by Luytens with monumental geometric yew hedges, complemented by a collection of large topiaries. The bones were in place.

The real gardener, however, was Daisy, who nurtured Christo’s early passion for plants–the only one of six siblings to have an interest in horticulture. Building on the structure so carefully laid by his parents Christo spent most of his childhood and entire adult life passionately cultivating a richly and idiosyncratically planted set of gardens, alongside writing dozens of books and countless articles on horticulture.

Today Great Dixter is operated under the Great Dixter Charitable Trust, established shortly before Christo’s death, to provide a platform for perpetual stewardship for the property. It is notable that Christo chose not to become part of Britain’s sprawling National Trust, opting for an independent public trust. While absent some of the safety nets of the National Trust, it was hoped this would permit greater freedom to shape Dixter’s future in ways that befit its idiosyncratic evolution. Fergus began as Head Gardener for about the last decade of Christo’s life and has since continued to develop the gardens with a breathless exuberance and sense of exploration and experimentation that Dixter has always embodied.

The symposium will have a profound and lasting impact on my own journey as an avocational horticulturist and gardener. I hope to return someday. It also appealed to my interests in organizational dynamics and institution building, in particular those in the first generation post-founder, which is effectively the case with Dixter with the transfer of leadership from Christo to Fergus. About 70% of small businesses fail in the transition to second generation ownership, and 50% of nonprofits (which Dixter essentially is as a public trust) make it to their 10th anniversary. While attending to the curriculum at hand I was able to spend some time talking to the staff about the operations and aspirations of the Trust. Based on these conversations–and setting aside the usual growing pains and human vagaries of organization–Dixter seems to be thriving under Fergus’s leadership.

What has been the secret to navigating this critical juncture? I think the answer is a strong culture of stewardship.

Beyond my interests in plants and ecology, I found Dixter redolent with the spirit and energy of stewardship and commoning values, even before its legal conversion to public trust. It was Daisy who first opened the gardens and nursery to the public decades before ceding to Christo. Yes, there were some financial motives (and lingering private interests), but ultimately those were focused on sustaining not profiting. And the ecology of Dixter was too rich not to share. (Today it is the third most biodiverse site in the entire UK.) After all, natural lands and ecosystems were commons before we imposed upon them human private interest. And despite our attempts to control and contain, they remain always a commons straining at the gates of legal and economic enclosure.

As I organized my reflections on Dixter, I identified eight threads of commons stewardship in ample evidence.

Sense of Place - While these principles are not necessarily ranked in priority order, I start with this one, which fast became the mantra of Fergus for our week together. Strong gardens are the result of a strong sense of place. This concept is perhaps the result of practicing according to most or all of the below elements; it could be seen as the culmination. While sense of place has been compared to garden designer Dan Pearson’s concept of reading the land, I think sense of place describes a more complex set of dynamics.

In the context of Dixter I understand this concept to have physical, metaphysical, and organizational dimensions. It is the physical disposition of garden spaces, landscape, and buildings, but it is also the history and memory of the place, and it is a set of values and ways of working–what today’s organizational theorists might call “culture”. In the case of Dixter, noted nonprofit management guru Peter Druker was right, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” Sense of place for Dixter means having a clear hierarchy of importance: plants, people, and then the buildings and artifacts, in that order. Christo maintained, “Plants come first at Dixter; the rest will work itself out.” A close second to this maxim, Fergus and his team maintain a commitment to movement, experimentation, trial and error, an allergy to stasis. Together these ideas and values come together to inform a multifarious but coherent and distinct set of practices that constitute the “Dixter way” and its sense of place.Pan-temporal Care - One of the defining attributes of stewardship is an awareness that one’s agency is situated in a temporal continuum that extends from a defined past to an indefinite future. There is a responsibility across time to people and the natural ecosystem that informs every major decision. This continuum transcends any modern notions of ownership or title holding. And as gardens and natural landscapes demonstrate intrinsically, pan-temporal care is not just about human interest, but the interest of the entire natural ecosystem. This awareness is evident in all of the folks who care for Dixter. In the physical world of Dixter this idea shows up most viscerally in how the elements of the property that pre-date the Lloyd’s arrival remain present: in the horse pond that has become a semi-cultivated natural water garden; the remnants of an ancient mote, now empty of water but filled with wildflowers; the former grazing meadows that are carefully managed to bring forth the rich seed stock and native flowers of the region; and the millenia-old woodlands of ash, hornbeam, and oak that are still coppiced today, as they were 500 years ago.

Coppicing is the ancient forestry practice of cutting trees to just above the root crown or “stool” allowing the plant to regenerate while opening the forest canopy to allow other understory species to emerge and replenish the ecosystem. These are coppiced hornbeam stools at Dixter, each hundreds of years old. While they regrow they are surrounded by deer foils made of the cut brush to protect the young shoots from being eaten.

Decentering Money - In stewarding the commons we must fight the incessant incursion of financial interest. Keep commoning and commerce separate, the saying goes. For the health of any commons, the reduction of stewardship decisions to financial terms will almost invariably lead to poor decisions. That said, the embeddedness of commons in contemporary market economies necessitates some attention to finance, but only with the awareness that commons must use currency only to provision those things that the commons itself cannot (or has chosen not) to provide. Dixter propagates nearly all of the plants it needs to maintain its gardens, meadows, and woods; it makes its own compost and engages in deep permaculture design at all levels of operation. A pure commons, devoid of the need for commerce, would be able to provide all of the physical and metaphysical needs of the animate and inanimate things in its purview–it is engaged in total stewardship. In reality, most commons do not have that luxury. Like most of its peers, Dixter raises money, and sells admissions, plants, and merchandise to fill the gap. But I would venture to say the ca. GBP 1M in budget needed to operate Dixter is substantially less than the total undocumented value of the resources generated entirely within its commons and the uncompensated human effort at core of its operations.

Centering Anarchy - Dixter is famous for the extraordinary density of its planting. In the words of Fergus, the reigning style is zany. The gardens are a vast menagerie of plants that have been left in a semi-wild state of cultivated chaos. Ornamental and native plants that in most gardens are kept under the careful control of their master have been permitted to naturalize throughout the property, with much of the management consisting of editing and subtracting layers of growth throughout the season. To be clear, this cultivated chaos actually takes a tremendous amount of effort to maintain, but there is also a comfort with letting the gardens and certain plants breach their imagined enclosures and wander. About 70% of Dixter’s gardens are semi-permanent perennial plantings interwoven with self-sowing species. The remaining 30% are allocated to an annual rotation of new plantings. Aside from the sharp edges of the topiary yews, the gardens cascade over themselves and spill out into the walkways. Part of being a good steward is not gripping the leash too tightly. You need to feel the natural push and pull of the thing in your care, let it lead, and know when to give it rope and let it run.

Gentle Mutuality - Scholars David Bollier and Silke Helfrich, write about the role of gentle reciprocity in commoning, the idea of an exchange of support and value that is not always an even tit-for-tat. It doesn’t balance on the ledger, in fact, there is no ledger. Yet the impulse and mutual sense of responsibility remains. I prefer the idea of gentle mutuality, as reciprocity, for me, connotes more of a transaction relationship focused on the act of exchange, whereas gentle reciprocity is a state of being in the world. That state of being is evident in the spirit of Dixter in its constant attention to giving to the world, from its local community, to an ever-growing group of visitors and gardeners that spend time learning at Dixter. And the world gives back. It is also core to the approach to caring for the gardens, woods and fields. Fergus has a long-standing educational exchange relationship with Chanticleer in Philadelphia (its apprentice gardeners train for a year at Dixter) and supportive relationships with dozens of other gardens and nature conservancies around the globe. You feel the clear presence of an international family of scholars, gardeners, conservationists, artists, and enthusiasts that are engaged in a relationship of gentle mutuality with each other and, of course, with the gardens and our natural world.

Observation to Awareness - A persistent theme of the symposium was the value of taking time to observe, whether your gardens, other gardens, or the natural world at large. A cultivated practice of simple observation allows you to tap into the spirit of a place and the constantly evolving lives of the people and plants that inhabit it. If you want to know what plants might thrive in Philadelphia in late summer, don’t read a book or catalog, visit other gardens at that time of year and see what’s happening. The phrase “building awareness” has become so overused in our world that it’s cliche. Awareness is a state of mind or being-in-the-world, not necessarily a state of action. In contrast, observation is an active state, applying concentration and focus, being intentional about the subject you are focusing on. Awareness is the product of observation, not the other way around. At the beginning and end of every day at Dixter, we had time to simply be in the gardens, to observe and read in. Even in the short span of a week it’s astonishing what transpires and what can be learned from plants, if you care to observe.

Eating Externalities - Any commons is subject to external forces and impacts. With the growing polycrisis of ecological, socio-political, and economic tumult and collapse, these are unavoidable. Yet many schools of management and systems design teach that organizations and systems should be fortresses, constantly building up resistance to things outside their control. Activities like strategic planning, risk management, and competitive advantage analysis are meant to enhance immunity to externalities, or permit the ability to “pivot” and avoid negative impacts. In reality, there is no immunity or avoidance with many of the forces at work today. A different set of tactics is needed, namely the ability to absorb the impact, process it, and let it transform the system.

The effects of climate change are alarmingly present Dixter: ancient specimen trees dying from desiccation, plants that no longer thrive amidst rising temperatures. The week of the symposium was at the end of a three-month drought with uncommonly high temperatures. Beyond the odd hose bibs positioned around the property, Dixter does not have an irrigation system, nor does it intend to install one. Fergus bemoans the loss of many plants that have fallen to storm and scorch, but the answer is to introduce new plants that can meet those challenges, not try to beat against the tide of climate change.Relentless Curiosity - Finally, none of the above is possible without a spirit of relentless curiosity. It is the essential predicate for embracing experimentation, success, failure, and change in general–all inevitable encounters in the gardens. At Dixter, the gardens are constantly changing with the introduction of new plants and plantings, in constant flux of combination and cohabitation. The nursery and garden teams engage in experiments, formal and informal, related to propagation techniques, the husbanding of species, and evolution of the ecosystem with new and rapidly changing environmental conditions. The vast network of exchanges and expeditions that the garden team regularly undertakes are fueled by curiosity about the natural world and the learnings that result. The day after our symposium ended, Fergus left for Turkey to accompany colleague botanists on a collecting expedition. It was Christo’s final wish that Dixter not become a museum to his life as a gardener, an object in a vitrine. He wished rather that it continue to evolve and change under new stewardship, driven by the principles above, the industry of its modest team, and the mutual care of its extended international family.

And indeed it has.

Coda

It is my own relentless horticultural curiosity that brought me to Dixter to learn and observe. Over the past four years, I’ve rekindled a childhood interest in horticulture and started work on eleven planned gardens (five are in progress) at Locus Solus, our home in the historic Overbrook Farms section of Philadelphia. The house was built on an acre of land in 1913 by Ernest Leigh Tustin, a lawyer, state congressman, and park enthusiast. We are working to restore the house and reimagine the landscape, but in the spirit of Tustin’s interest in parks and gardens.

In my opinion, the Small Water Garden, while the youngest and smallest, is the most successful so far. We built and planted it over August/September 2022. It is a dense mix of largely of native North American and Asiatic species, my own zany answer to the surgical restraint of traditional Japanese garden design.

You continue to astonish me with your blending of horticulture and the concept of communing. I, at the moment, have lost control of my iris population -- bought five during a brief time of anxiety and impulse. They came. Sarah got the in the ground and the next week 12 more came I had forgotten that I ordered more carefully last fall. I would up giving five of them to Jerry, who has his own garden projects that are keeping him busy. Carry on!