"You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means."

– Inigo Montoya

The Productizing of Language

The creation of lingo–terms of art with particular meanings within a field or affinity group–is part of the social bonding and truth-claim manufacture of all fields of human endeavor. In this activity, the nonprofit sector certainly holds its own. In the nonprofit world, lingo is largely manufactured by academics and consultants to lend weight, substance, and value to ideas they want to sell to their audiences or clients. In most cases, lingo-making is the process of dressing old (but often important) ideas in new couture, adding shine and pizazz to a concept, allowing it to trip more impressively off the tongue at conferences, in the conference room, or over cocktails. Lingo transforms ideas into products with currency and wraps them in the urgency of fabricated novelty. We are all complicit in this process, either as inventors or users of lingo, or both. Either way, we crow like a rooster taking credit for the dawn.

The problem with lingo (and for that matter, all language) is that its creation is marred by unconscious assumptions about how the world works, or in my field, how nonprofits operate (or might operate), as well as lack of forethought about the full spectrum of a word’s denotations and connotations. Our era of soundbites and social media is one of widespread linguistic carelessness and disregard for precision in the words we choose and meaning we seek. As a result, the use–or misuse–of language can foreclose on possibility, limit conversations, and otherwise blind us from seeing the world in a new and different way.

This is true of one of the most overused and under-thought terms in the nonprofit sector: collaboration. Our current use of this term, contrary perhaps to intentions, is inhibiting the broader conversation in our sector around how we move beyond the dominant approach to building nonprofit capacity–every mission needs its own stand-alone infrastructure–to a future sector where the norm is a plurality of missions and agency sharing management and core capacities, or management commons.

Confusing Collaboration with Commoning

Over my two decades working in the nonprofit sector, I’ve heard with growing din and cadence, the call (or command) from philanthropy for nonprofits to collaborate. In more recent years, this call has reached a fever pitch, everywhere in one form or another the preference or requirement of grantmakers. It is one of the most enduringly fashionable donor restrictions of our time. But whenever I hear philanthropy issue the command, “Collaborate!”, my mind goes to the famous bit from The Princess Bride, where the Sicilian kidnapper Vizzini, always confounded, exclaims, “Inconceivable!”, to which his accomplice, Inigo Montoya responds quizzically, "You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means."

Behind the drive toward collaboration from funders I hear clearly, “We want you to collaborate so that we can pay half as much for double the impact.” It comes off as a knee-jerk and facile response to the economic impossibility of philanthropy. The reality is that at any given time, the horizon of need and general do-good agency out there vastly outstrips even the $1.2 trillion in endowment parked on Wall Street, let alone the fractional amount of interest that actually moves to nonprofits in the form of grants. This macroeconomic reality is coupled with philanthropy’s self-induced social mores and pressure to spread their money around, whether in the interest of political appeasement, noblesse oblige, mission-based stock picking, or the persistent malaise of Donor Attention Deficit Disorder (DAAD). Together these forces encourage any scheme that might stretch the charitable dollar. Collaboration has become a perennial favorite.

The only problem is that collaboration does the opposite of save money, no matter how hard you squint at a set of blurry economic assumptions. In fact, it consumes more money and time than not collaborating. The Oxford English Dictionary defines collaborate, “to work jointly on an activity, especially to produce or create something”. Collaboration entails two or more people or organizations working together toward intentional goal(s). They may be sharing some things, such as complementary skills and aptitudes, community relationships, or physical and material resources. But in the end, when it comes to money and its equivalent, human time and effort, getting complex systems of people to move in a shared direction takes substantial additional cost inputs. While many may think the collaboration equation is 1 + 1 = 2, it’s really more like 1 + 2 + 1 = 4.

And don’t fall for the “whole is greater than the sum of its parts” rationale for collaboration. It’s never 1 + 2 + 1 = 6. The whole is always equal to the sum of its parts. Lavoisier’s Law of Conservation of Matter applies equally to organizational dynamics: just as matter can neither be created nor destroyed, so goes it with organizational time and money. The “whole is greater” idea is simply misusing an economic metaphor to describe the often unique outcomes that arise when organizations work together. Don’t get me wrong. Collaboration between organizations can yield great benefits, largely in the form of being able to do things together that may not have been possible individually. But we cannot confuse such extraordinary or collective outcomes–which may have great social worth irrespective of cost–with an assumed economics of efficiency.

There is, however, a collective way of managing shared resources that does deliver (lower) cost benefits while supporting mission and impact impact. What philanthropy may be after is, in fact, commoning, but owing to a general lack of awareness and understand in the nonprofit sector of these areas of practice, collaboration is persistently confused with commoning.

Commoning is the active sharing and stewardship of a defined set of resources by an open but defined group of people or institutions. As such, it is closely related to cooperatives with regard to shared governance control, stewardship, and other values. But unlike cooperatives, true commons resources are not owned privately, nor are they owned by the state, or nonprofits sectors. In fact, we don’t have a legal or ownership construct for commons in the U.S., so as a default they are usually either government or nonprofit-titled resources. Despite this legal deficiency, commons allow multiple individuals or organizations to steward collectively resources that benefit all of the sharers, or “commoners”. Commons resources may be defined along very diverse lines: real estate, natural lands, technology, know-how, financial assets, and yes, nonprofit infrastructure and management.

Commons don’t exist without the active process of commoning. They need to be governed and stewarded through mutually agreed upon rules about how resources are accessed and maintained, accountability principles to address bad actors, and other provisions. Economist Elinor Ostrom won the Nobel in part for her sociological work in codifying the Eight Principles of Commons Management. In the end, a commons is a shared resource that does not require active collaboration among those who share it, just a set of governing principles, and a commons manager.

The shared resources of a commons can offer sustained economic and provisioning benefits to those who share it without the added time, effort, and financial cost of collaboration. For example, in the nonprofit sector, commonized corporate, management, and other core infrastructure can allow multiple independent missions to share a common backbone without the organizations having to give up their individual identity, agency, and vision. This is essentially the work of fiscal sponsorship, in particular the comprehensive form. I view fiscal sponsorship, in its most equitable and just form, as a commonized management resource and permanent operating solution that can be shared by multiple independent change agents and organizationals–a management commons.

The example of fiscal sponsorship offers a powerful illustration of the economic benefits and efficiencies of commoning alone, absent collaboration among organizations. Economic analysis done by my organization, Social Impact Commons, has shown the potential for nonprofits to reallocate roughly 10% (or more) of income from needlessly duplicated back office and corporate costs to front-line programs and services, if only organizations shared that infrastructure through a comprehensive fiscal sponsor.

The study examined roughly 1,000 stand-alone arts and heritage organizations in Pennsylvania and California operating below $2 million, comparing what they averaged individually in back office costs (17% to 27% of revenue) with the equivalent shared backbone costs of a comprehensive fiscal sponsor (which usually allocate 10% to 15% of revenue for their shared support), an average difference of 10%. Looking at other overhead studies for the sector, which found nonprofit overhead for other fields to range far greater than 27%, we consider the ca. 10% “back office savings” to be definitely on the low end. To widen the lens a bit further, total throughput for the nonprofit sector is north of $2 trillion. If just a quarter of the sector (ca. $500 billion) managed through such commons infrastructure, about $50 billion annually could be allocated away from overhead to direct programs and services.

Now just imagine taking all of those stand-alone organizations operating below $2 million (which is the budget range of about 90% of the entire nonprofit sector) and having them collaborate, adding yet more time and financial cost to the already needless duplication of infrastructure that burdens the sector. That’s certainly not stretching the charitable dollar! That said, it’s worth noting that any commons can permit two levels of participation: just commoning (alone) and active collaboration among commoners, so you can get the best of both worlds. But the important thing is that the economic benefits of commoning can be reaped without forcing collaboration, leaving such intentions to when and where they are warranted or desired.

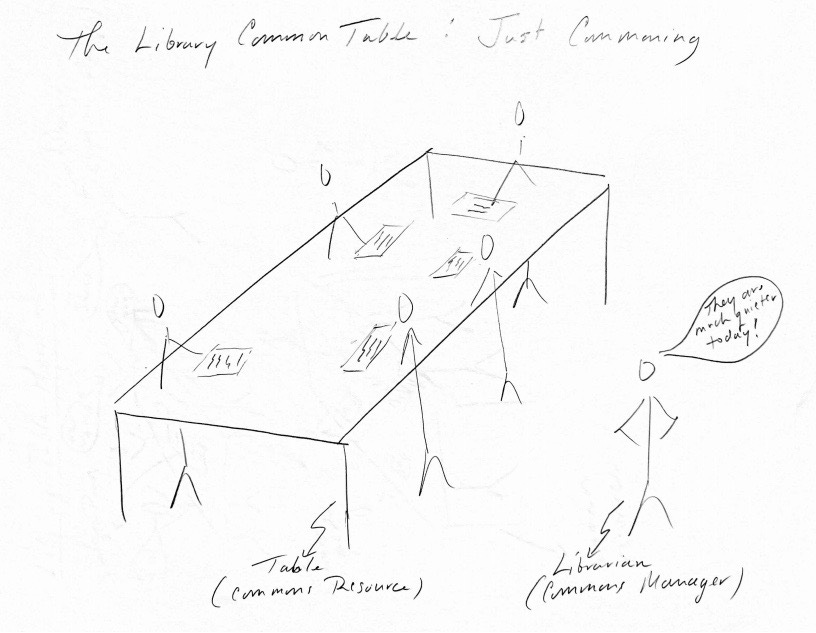

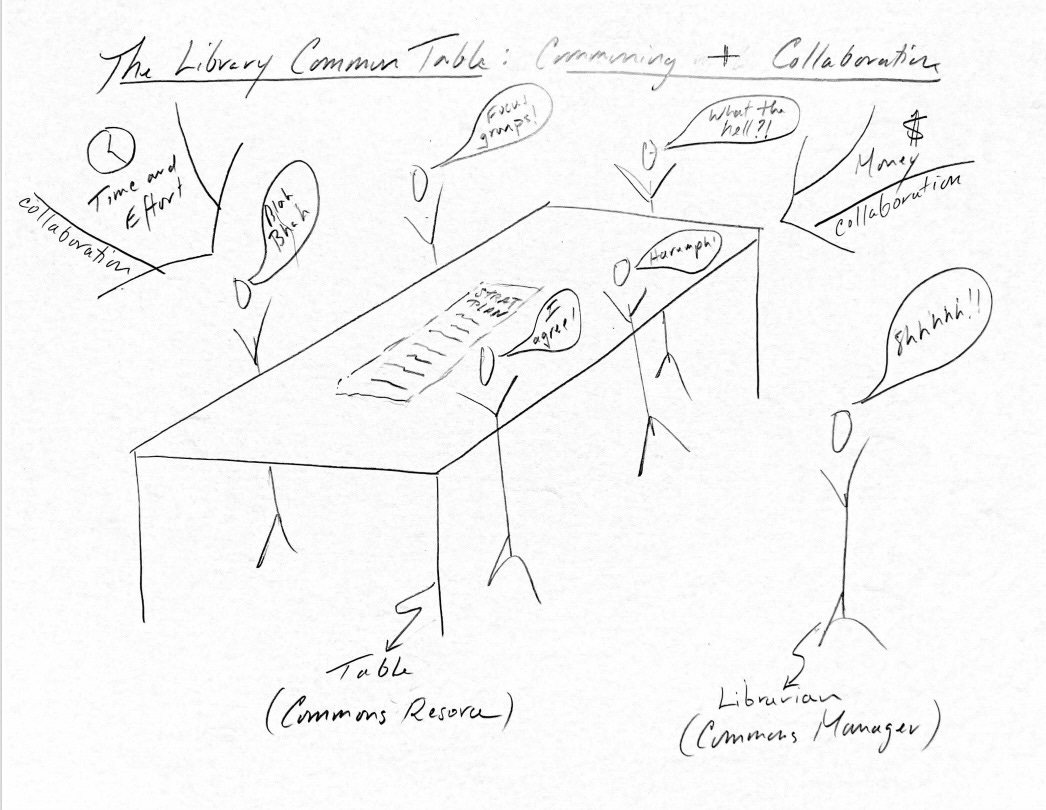

In closing I offer a summary comparison of commoning and collaboration using my favorite facile metaphor, the Library Common Table. Forgive the goofy renderings. I’m not an artist, but I decided to entertain myself…

For just commoning, the table is the commons resource, and the librarian the commons manager, setting rules and making sure the commons resource is well maintained for the commoners. Five commoners are at the table attending to their individual work. Each benefits from use of the table, but they are not actively collaborating. In fact, they don’t need to have any relationship with each other at all to enjoy the benefits of the library space and the table.

A different group of workers might use the same common table for a collaborative meeting. In this case, they are reaping the benefits of the shared resource, which doubles as a platform (literally and metaphorically) for their work on a strategic plan. But while they might be realizing efficiencies through commoning, the attention of their collaboration consumes additional time and financial resources.

In either case, commoning affords a mode of sharing that has benefits regardless of whether the folks doing the sharing have a working relationship with each other.

So before writing yet another request for proposals asking for collaborative solutions, grantmakers should stop and ask themselves, “Is it really collaboration we’re after, or might it be commoning?”. I would hope that greater attention to and understanding of the differences might usher in a new area of philanthropic focus, one of direct support for commoning solutions, such as management commons.

Inconceivable? I think not.