It is a space beyond, below, above, and otherwise outside of our current frameworks that both define and permit possession and control, namely those of the state, private, and charitable spheres. It is a space that transcends time, having existed since “before the before”, in the words of Fred Moten. And it will be until after the after, plus ultra. In the Undersector, our responsibility to each other, the world, and its resources are defined exclusively by mutual stewardship. Borders and boundaries are fluid and title holding vanishes into the aether. It is a world bound together not by entitlement and enclosures, but by the individual and collective necessity for care that results from their absence.

Why this name? To answer this question we have to define sector, for our purposes, in an economic sense. It is a rather diffuse term today, referring to a range of ways in which we talk about parts of the economy. Sector is used as a synonym for terms like field, industry, business model, and so on.

Economically, sector describes a category of owner and ownership, or more specifically, possession, from the root possesses, “to hold in one’s control”. A sector describes a type of possessor, including the particular reasons, rights, responsibilities, and obligations that come with that possessing. Today, there are three recognized sectors: the state (or government), private, and charitable (a.k.a. nonprofit or civil society). Today, these three sectors are recognized globally, with equivalent legal forms and financial policies established for most countries. It is the strong parity, international recognition, and transnational linking of these sectors that has facilitated the creation of our contemporary global economy over the last century.

Recognition of the three sectors might imply crisp distinction among them–clear boundaries, borders, and rules of engagement for exchange and commerce between them. The reality, however, is far from a tidy and clearly differentiated coexistence. Borders have been breached and territories occupied, largely by the most cunning of the three, the private sector.

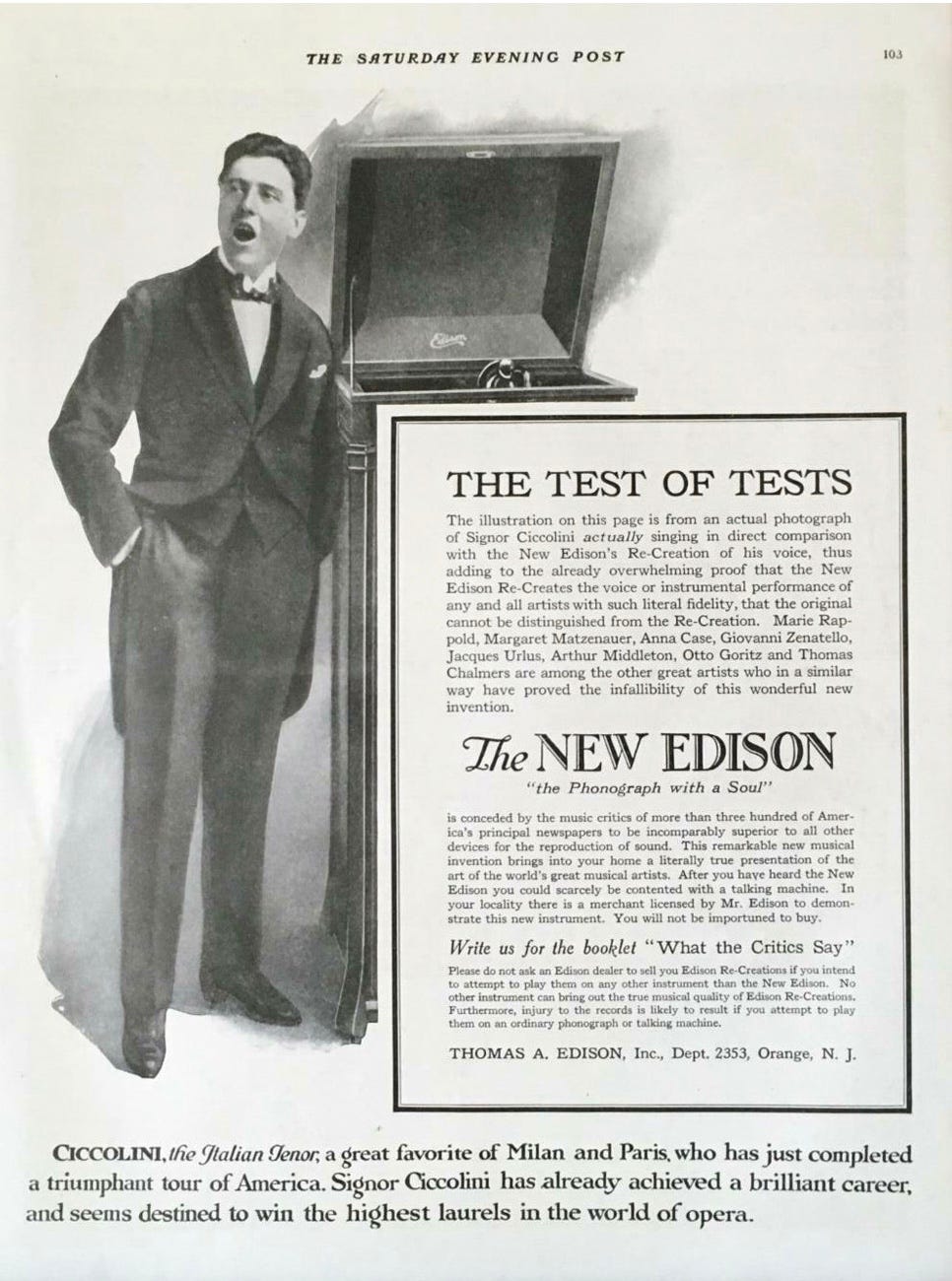

The introduction of Thomas Edison’s Diamond Disk phonograph in the second decade of the 20th Century ushered in the concept of “tone” as a standard of fidelity between live and recorded sound. Long before the tag line “Is it live or is it Memorex?”, Edison made a spectacle of seeing if people could distinguish between a live singer and his machine. Writes historian Emily Thompson, "Between 1915 and 1920 the Edison company sponsored over four thousand tone tests and twenty-five different sets of artists were scheduled to perform more than two thousand tone tests in 1920 alone.” Shocking from our contemporary auditory standpoint is that most could not distinguish between the singer and the mono recording playing next to him. It turns out that such an ability is learned, as is our ability to discern other kinds of difference in the world around us.

The private sector has inveigled, invaded, and otherwise bullied its way into the state and charitable sectors. Like any colonizer, it has pursued its interests through replicating its values, customs, rules, and manners within its neighboring sectors, at times through tactics of subtle induction and acclimation, at times through campaigns of violent force. This invasion has accelerated over the last several decades with the rise of neoliberal economic policy and its frequent bedfellows, autocracy and oligarchy. The methods and manifestations of this incursion and its problematic consequences will be much of the territory I will be exploring in future posts.

Since the advent of the modern era, private interest and its creations, the free market, business deregulation, and debt as a tool of enslavement and extraction, lie at the roots of most if not all of the ills we face as a global society and as stewards of this planet. While free enterprise may not be harmful in all of its manifestations, today’s global, market-driven economy, largely unfettered from regulation, is failing to address the most urgent problems of our time: wealth inequality, poverty, mental illness, and the biggest of them all, climate change and its threat to life on earth. And it is worth noting that even with the best intentions, extraction in general, regardless of the resource (labor, time, cash, timber, and so on) is inherently an act of violence and harm.

In more recent history, the key counterbalances to the extractive effects of private interest have been the state in the form of regulation and investment in non-lucrative activities that the market refuses to address (e.g., conservation of natural lands, renewable energy, certain aspects of healthcare research, etc.) and the nonprofit or civil society sector. The latter has been fashioned as a proxy of government, hence it doesn’t pay taxes, doing social benefit work that the government would otherwise have to do. Viewed from the vantage of the private sector, the charitable sector is there to support work and preservation of resources that are essential to healthy society and life on earth, but that the market will not or is unlikely to support. In this manner the charitable sector exists as both a refuge from and counterbalance to the negative forces of rentier capitalism. (The term “rentier” here and forward is used in the economic sense, indicating the pursuit by private interests in net income/gains or “rents” off of labor or other assets.)

If the state and nonprofit sector are there to protect us against the worst of rentier impulses, what happens when private interest takes over the nonprofit sector and the state? Both become servants of the private sector, challenging or negating the ability to offer any counterpoise. At this point, you may be thinking that I’m advocating a purging and cleansing of the state and nonprofit sector–a conservative return to a purer, original form–in order to refurbish them to their function as more wieldy impediments to the excesses of neoliberal capitalism.

If only it were that simple.

First, today’s sectors did not simply spring forth in the pristine and idealized forms suggested above, bearing the insignias of good and evil, ready to do battle. Their histories are intimately intertwined and complex. The creation of the United States and its laws and government out of the act of American independence was in great part motivated by interest in enabling the power of private interest and enterprise, not just the popularized motive of religious freedom. In many ways, the U.S. state was originally designed by and for private interest. It is only recently, in the social policy of the post-WWII New Deal, that our government was reimagined as a guard against economic inequality, environmental disaster, and the abuses of corporate interests. And that vision for government has been greatly diminished over the last forty years by the forces of Movement Conservatism and the Religion of Neoliberal Economics that holds faith in the power of unfettered markets and private innovation to solve our most pressing problems.

Second, the nonprofit sector is principally fueled by the financial residue of rentier capitalism, namely philanthropy. This alone makes its design and motivations complicated and suspect, at best. It exists as a consolation for the negative social and economic impacts of the private sector, the great apology of the wealthy. The laws and regulations governing the charitable sector are more concerned with ensuring that it never competes with private interest and less concerned with enabling it to do work at scale to clean up the mess left by unfettered rent-seeking. These and many other attributes, often ignored or simply accepted as unquestioned reality, lie at the heart of my interests.

At the end of the day, there is ample evidence that the histories, interrelations, and current entanglements of the state, private, and charitable sectors likely render them unrecoverable and to a great extent, indistinguishable when it comes to the imprimatur of private interests. And to reckon a way forward for social good using such a dirty and damaged lens may send us only in circles.

For this reason, we need to begin to imagine a sector beyond, before, and after these three, the Undersector. I would assert this is a place we all know well, in fact, but overlook in our daily movement through the world. It remains just outside of or under our view. Our work is to see again, to bear witness to its values, customs, and presence. We must remap its territories, rediscover its artifacts, relearn its rituals. This is our journey together.